Portrait Man in Pink Suit National Gallery of Art

Due west hen information technology comes to wielding a pencil, an etching needle or just a felt pen, David Hockney has no rivals. Lucian Freud's etchings bore me senseless, Francis Salary barely doodled, simply Hockney is a graphic principal. His retrospective of a life of portrait drawing is the most dazzling brandish of his art I accept ever seen.

Forget the rants nearly smoking, or the personality that has always made him so lovable. Hockney hither is not a star but a stare. In self-portraits fatigued with a steady black line, he eyeballs himself in the mirror, mercilessly seeing lank hair and a skinny body. He draws his ain eyes through the unforgiving lenses of his spectacles. It's uncomfortable to stand close to those eyes – the sense of Hockney sizing you up is virtually oppressive. This series was fabricated in 1983, when he was still blond, but he can run into himself getting older. What does the hereafter hold? The intensity of Hockney's self-inspection, fag in mouth, bears comparison with Rembrandt. When an creative person looks and then hard into the mirror, we share what they see – nosotros are invited into the undisguised truth.

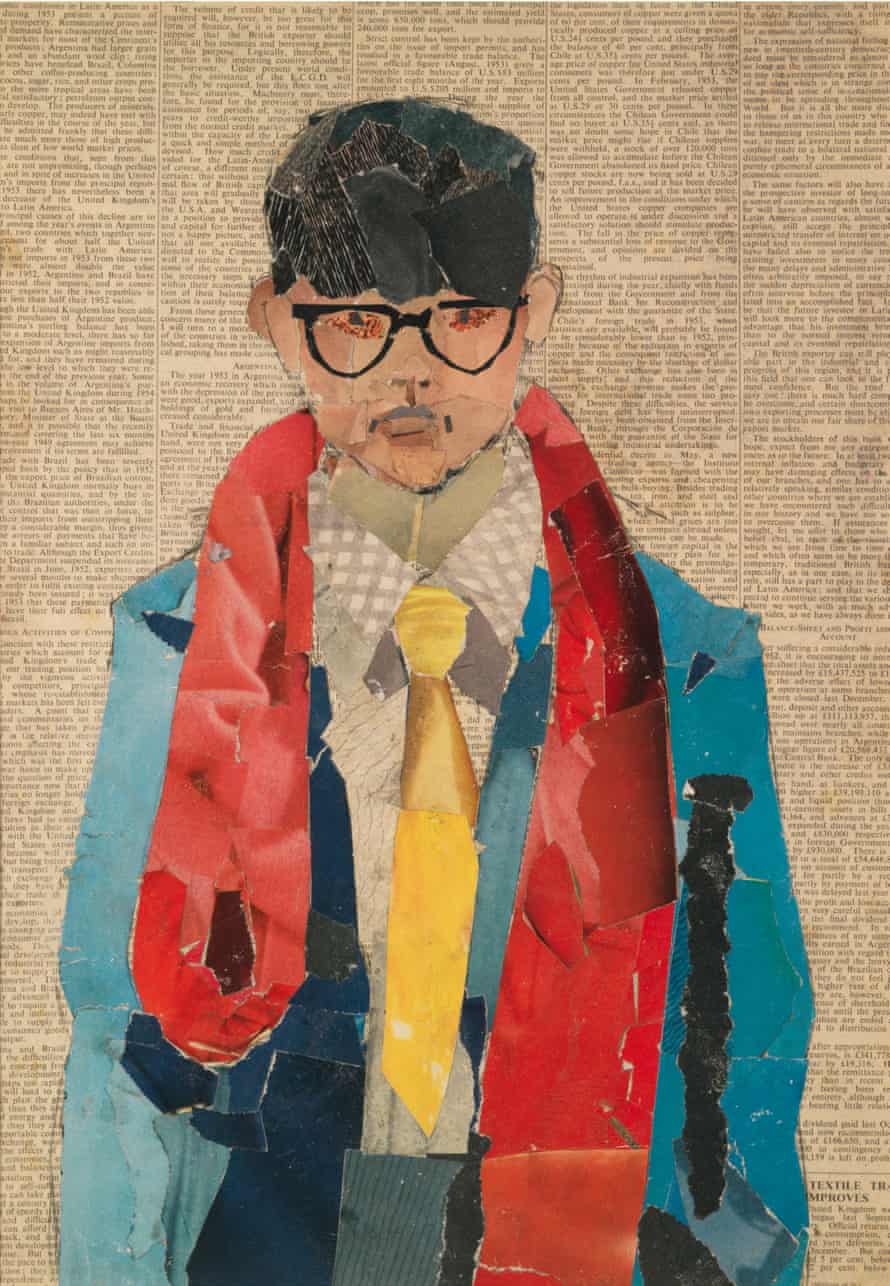

Hockney has been looking into the mirror since he was a teenager. In drawings and a lithograph from the 1950s he scrutinises a serious, sensitive youth in a brownish pullover, with chocolate-brown hair. (He'southward already got stylish glasses, though.) These self-portraits done betwixt the ages of 17 and 19 prove Hockney had immense power earlier he went to the Royal Higher of Art. But what makes this exhibition and so staggering is the moving picture it builds of a human who has never stopped learning. The reason cartoon suits Hockney is that it lets him test himself. His lack of self-approbation is what makes him so fallacious.

Picasso is his restless instructor. In 1973-4 Hockney portrayed them together in a fantasy scene that emulates Picasso'south Vollard Suite. Pablo sits on one side of a table in a stripy top, while Hockney faces him, nude, to be sketched. His pubic hair fluffs up betwixt his legs. It's a wonderful dream – to be Picasso's nude – but Creative person and Model could just every bit well have been called Master and Educatee. Folded defunction and a view of a French street are defined in thin, strong black ink lines in the style of Picasso's portrait of Igor Stravinsky. It's very hard to draw equally merely as that. Picasso got the manner from Raphael. Hockney has the same conviction. And like Picasso, he plays games. This is the lesson of the principal: you need to change style constantly in the search for an elusive truth.

Since the 1960s, Hockney has done just that in portraits of iii of his closest friends: Celia Birtwell, Gregory Evans and Maurice Payne. Each gets their own generous infinite. Birtwell'south beauty is recorded with seemingly endless stylistic fun. Sketches from the 1970s describe the material and fashion designer, who was married to Ossie Clark, looking similar a glam dream in swanky dresses and romantic hair, drawn in soft colours. She poses with a cigarette, or lies dorsum in Paris in a skid, her face a mask. Maybe it's her enigmatic aura that made him draw her so often. Even so she doesn't concur anything back – Celia, Nude, which dates from 1975, has her wait abroad while she lets Hockney describe her breasts orange and blue.

Gregory, also, let Hockney depict him naked in 1975. In Gregory Leaning Nude, he looks similar a Florentine youth painted past Botticelli. He rests his slim body against the wall, looking into infinite from under long tawny locks while Hockney records his pinkish penis. The following yr, he closes his optics for a lithograph in which he'due south wearing just gym socks. Merely while Hockney tin can make Evans beautiful, he has also drawn him in states of scary vulnerability. In ii studies from 1988 he seems damaged. In a 1999 portrait his hair is mangled and sweaty, his face desperately emaciated. Evans is Hockney'southward lowest, undergoing life'due south changes, who, in these works of fine art, experiences farthermost highs and lows. A loving written report of him asleep adds to the novel of his life.

With Payne, the theme is time. In 1967, Hockney drew this handsome man equally a dandy. Past 1984, he was ageing and meditative. And through the 1990s, Hockney recorded each mark of fourth dimension, in frank studies of a beautiful man getting on in years.

Every bit have they all. In 2019, Hockney brought their portraits up to date for this testify. Their latest ink portraits are shown together to intensely haunting effect. It's like the end of a picture where you lot come across the characters as they are at present, long later on their youthful adventures. Evans is in a tracksuit. Birtwell still has joy in her eyes.

Ah, and young David. What has go of him? A video shows his wrinkled hand leafing through an album of sketches from last year in Normandy. Their freshness and variety is staggering as he leaps hands from the most direct observation of forest-framed houses to abstract jeux d'esprit.

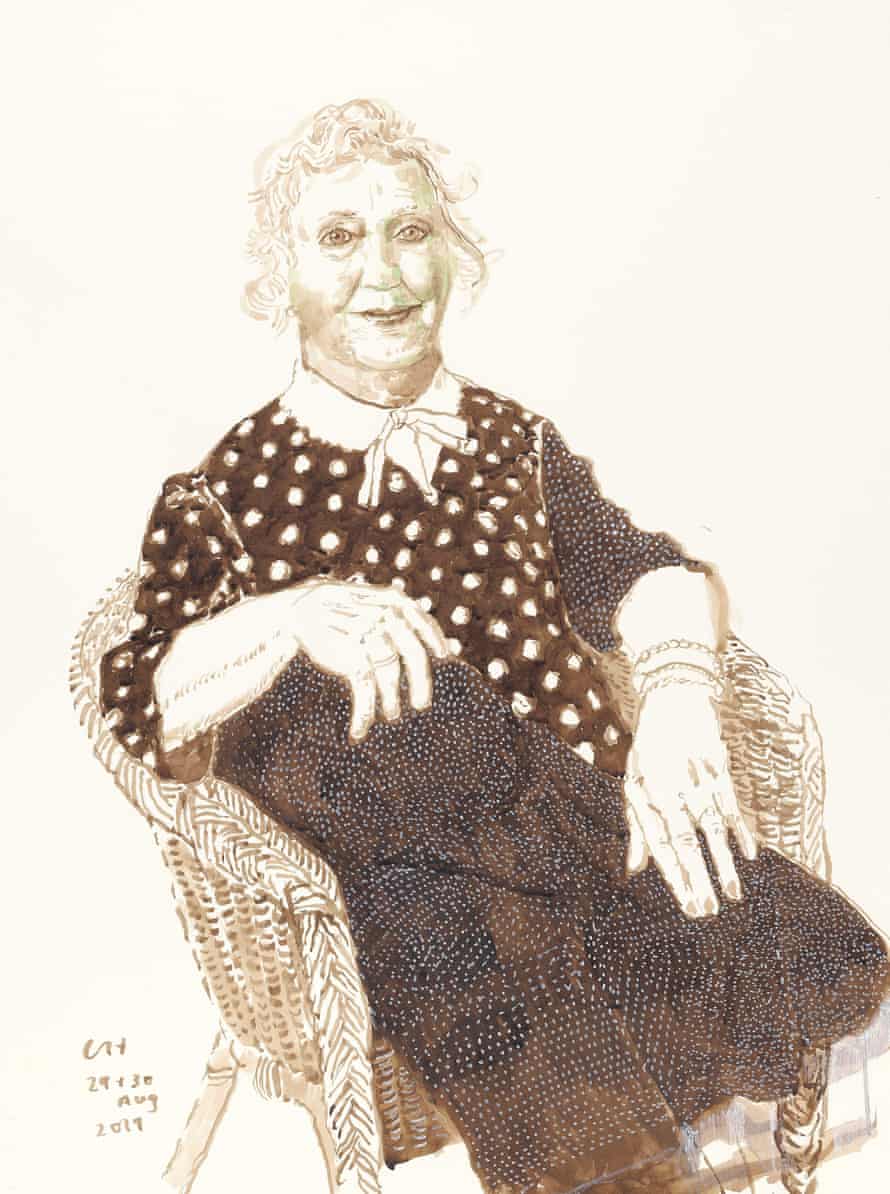

Wherever he is, you see, Hockney's true home is his sketchbook. Drawing lets him hold what he loves. A room is given to his acute drawings of his mother, once again resembling Rembrandt as he contemplates her in old historic period. Another set of images show himself to himself on his iPad – smoking and staring, screwing up his face up in a caricature of rage.

This exhibition reveals, with total freshness, an creative person full of curiosity about himself and other people. Hockney rejoices in invention but never loses sight of his simple subject: being alive.

-

At the National Portrait Gallery, London, from 27 February to 28 June.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2020/feb/25/david-hockney-drawing-from-life-review-national-portrait-gallery-london

0 Response to "Portrait Man in Pink Suit National Gallery of Art"

Enregistrer un commentaire